The Farm

As I toured Pure Country Farm I was struck by the smell. It smelled like hay and dirt. Not like 1,000 pigs. While pigs might roll in the mud (and sometimes poo), it’s to keep themselves cool and their skin protected from the sun. Which is important when you are fair skinned and do not sweat. They do not poo where they eat and are actually quite clean, intelligent, curious, playful animals. On a scale of one to ten, Paul Klingeman, Jr., my guide for the day, owner of Pure Country Farms, farmer, mechanic, truck driver, pig farmer and of course his own harshest critic, rated his hog farm an eight. Why not a 10? “It’s too big,” he said. Pure Country Farms is in an elite 3% of ranches and the first pig farm in the nation to receive the Food Alliance certification, meaning they adhere to humane and sustainable practices for raising animals – practices like access to water and sunlight and fresh air. They are certified organic and Prop 12 compliant (a California certification of stall sizes for a mama sow). They are a “never ever” farm which means they never use GMOs, added hormones, M-RNAs, and only ever use antibiotics when an animal is sick (and at which time is pulled out of the never ever program). They grow 85% of the feed they use, fertilizing the grain fields with the stock’s manure. They also raise beef cows. Paul Sr., Klingeman’s father, started raising pigs when he was 14 years old as a 4H project, and when he decided to make it his business, it seemed like the only way was as a conventional farm. Klingeman said he remembers the smell and humidity of the farm they had near Othello, before they had the opportunity to move to their current location near Ephrata. “We realized that wasn’t the way we wanted to do it,” he said. The opportunity to move, along with the opportunity to sell niche product in larger markets (Portland, Seattle areas, etc.) swayed their decision. Another eye opener: “We had someone who was allergic to a lot of things, and hadn’t ate pork in years. They asked us to use non-GMO feed for the pigs, and they were able to eat pork for the first time in decades. It was a really good feeling.

It allowed us to take a step back and ask how do we do it,” he said.

How they’re doing it is at once the most traditional way – a good ol’ family farm – and cutting edge. “Someone in my family is touching that animal at some point from birth to harvest… we know everything that is going into that animal,” he said. Along with Klingeman and Paul Sr., the farm is also ran by his mother Karrie, wife Melissa, three sons Barret, Nate and Rowdy, sister Laura Smith (more on her later), brother-in-law Turrel and their two kids Kenzie and Derrick. “My big goal on the family farm is that every kid can be part of any part of the farm and make it their own,” he said. And if whether it be at the farm or otherwise, he wants his kids (and maybe just all people in general) to, “be happy with what you’re doing. Enjoy what you’re doing.”

Often, Klingeman said, farms and ranches put profit before the wellbeing of the plants and animals they raise.

In the Midwest, mostly Iowa, where most of the nation’s hogs are raised, pork is a different beast. “They bred it lean, they bred it for confinement, and they bred it for efficiency and they bred it for cheapness… and the sad part is that’s what the industry was calling for. I’m not bashing other farmers, this is the way we wanted to do it and are lucky we found enough demand locally to allow us to do it,” Klingeman said. In Iowa, where farms regularly raise upwards of 3,000 sows, his farm at 200 sows, would barely register. Here in Washington, Pure Country is the largest hog farm in the state.

An eight? Hogwash

“Hogwash” is the term Klingeman uses for many common practices in the food industry. Like how commercial meat producers add water to meat after processing and before packaging, or the words “natural” and even “family farm”. “We all assume too much and we all assume someone’s doing the right thing. And then all the big companies say too little. They’re not telling you everything – it’s all a big game to them,” he said. He also uses it in refence to many of Pure Country’s certifications because he thinks they do not go far enough to ensure the overall health of the animals nor quality of the meat being raised. He said if you can’t visit where your food is being raised, you don’t get the full picture and you can’t be sure of its quality. “Gosh darn it, go visit it [the farm], go see that they’re actually doing what they say they’re doing,” he said.

Pure Country sets their own standards based on compassion and science. By growing and regulating the quality of their own feed, they ensure a high yield of the tastiest meat. By redesigning their sorting ramp into stress-free automation, they’ve reduced the stress on their pigs and extended the shelf life of their product by more than two weeks. Klingeman said they are ultimately looking for the happy medium of affordability and sustainability: what’s best for the animal, the consumer and the environment.

That can be a difficult area to land in, as well. Last year, Pure Country paid out $100,000 in third party audits for their certifications. Certification can be tedious, as well, with every carcass requiring non-GMO certification, as well as each cut that comes from it.The Store

The altruistic model of Pure Country Farms would be at a loss without its other half: the Pure Country Harvest storefront. The storefront is how the farm is able to get its product out directly to consumers without paying a middle man or following export prices. It is an important feature of their “buy local” standards, because if you buy organic meat in the grocery store, it can come from as far away as New Zealand and offset any ecological benefits with the around-the-world transport.

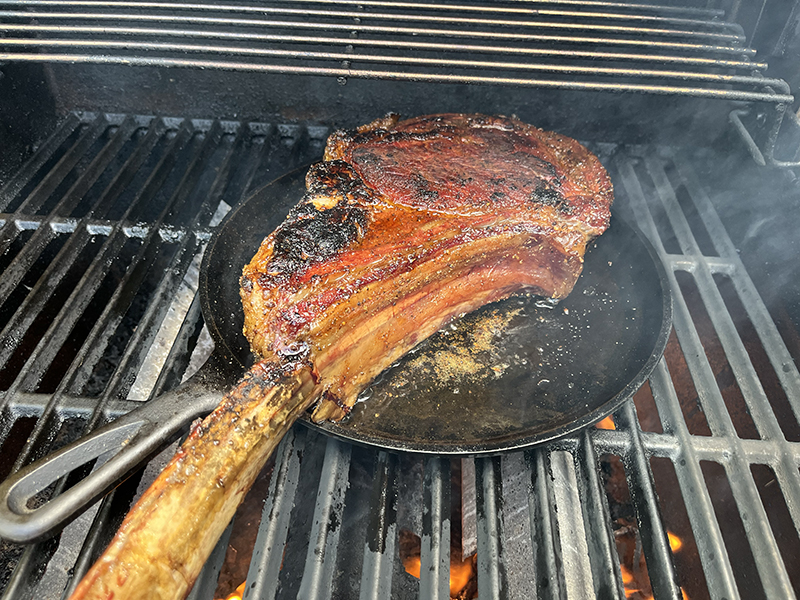

Klingemans sister, Laura Smith, mentioned earlier, runs the retail shop in Moses Lake, where us hungry folk can purchase delicious aged bone-in porkchops, impressive 3.5 pound bone-in ribeyes (commonly known as Tomahawks), breakfast cuts, ground beef, all the way up to half cows or pigs. Also for sale at the shop is organic produce, locally raised chicken products, Pure Country swag and select other items.

Smith said buying and selling bundles is just one way they keep costs low for their high quality products: a “half hog” is $450 and includes 75 pounds of meat, plus five pounds of sausage links thrown in for good measure. “I want people to feel like they’re getting a good amount,” she said. A half hog is likely to last a family of four about six months. And as Klingeman pointed out, since their products are not injected with additional water or color after producing, the per-pound cost of their product is comparable to what you would find in the grocery store.

Ultimately, every buyer has to decide what they need from their food – is it organic? Non-GMO? Raised humanely? Low cost? Whatever it is, Pure Country is what they say they are – a family farm raising delicious and healthy products. That’s not hogwash, and they can prove it.